Highlights from the IFPRI Policy Seminar, “Tackling Extreme Poverty & Financing for Food Systems in Africa” (October 2025).

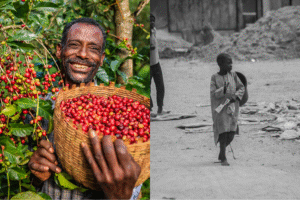

Between 2018 and 2023, eleven African countries, including Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, and Kenya, received almost half of all external financing directed toward food systems on the continent. Yet, according to the World Bank–UNU-WIDER analysis previewed at IFPRI’s policy seminar, Nigeria and DRC are projected to host a quarter of the world’s extreme poor by 2030. This implies that Africa’s largest recipients of aid are also its most persistent poverty hotspots. This paradox captures what we at Graft Africa have termed “the junction of abundance and absence“: an uneven landscape where capital pools but transformation thins, and where fragility remains both the cause and consequence of financing asymmetry.

Many crucial insights emerged from discussions at the policy seminar with ramifications in both policy and practice. At Graft Africa, we have synthesized them for dissemination to our communities of knowledge and practice, partners, and the wider global development community, all of whom these insights rely on to be translated into strategic action.

1. The Paradox of Expansion without Escape

The Africa 3FS Report on External Development Financial Flows to Food Systems (IFAD, IFPRI & AKADEMIYA2063, 2025) records that Africa received roughly USD 117 billion in external food systems financing between 2018 and 2023 – about 40 percent of global flows. The figures suggest priority and attention to the issue area yet the poverty data tell another story. During the same period, the number of people living in fragile or conflict-affected contexts worldwide surpassed one billion, and 71 percent now reside in Sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank & UNU-WIDER, 2025). Extreme poverty in those fragile African states has more than doubled since 2005, reaching roughly 451 million people in 2024.

This means that despite growth in funding volumes, the continent’s poverty geography has not shifted outward but deepened inward. What appears to be progress in resource allocation conceals a widening gap in structural transformation, signaling a paradox of expansion without escape.

2. Fragility as financing architecture, not only context

“Fragility is now at the center of the world’s poverty situation” – Luis Felipe López-Calva, Global Director, Poverty Global Department, World Bank Group

A recurring theme across both presentations at the seminar – the Fragility at the Core of Global Poverty (World Bank & UNU-WIDER, 2025) and the Africa 3FS Report (IFAD, IFPRI & AKADEMIYA2063, 2025) – is that fragility is no longer peripheral to Africa’s development challenge; it has become its organizing geography. Fragility is not only an outcome of conflict or weak institutions. It is also embedded in the architecture of financing itself. Three aspects illustrate this dynamic:

- Concentration without coordination: External finance flows are heavily skewed toward a few large recipients and toward project types that are easier to disburse quickly, such as agriculture and value-chain development (≈39%) and social assistance (≈23%) (IFAD, IFPRI & AKADEMIYA2063, 2025). Meanwhile, the environment, natural resources, and data systems together attract barely 10%. This imbalance reinforces a cycle in which short-term relief absorbs capital at the expense of long-term resilience.

- Dependence without diversification: More than four-fifths of Africa’s food systems financing still comes from official development assistance (IFAD, IFPRI & AKADEMIYA2063, 2025). Concessional loans and blended-finance instruments remain modest, and domestic capital markets rarely feature in agrifood investment strategies. Therefore, when donors pause, the pipeline stalls.

- Volatility without visibility: Disbursements fluctuate with global crises, commodity prices, and donor priorities. At the same time, many national and subnational systems lack granular data to inform spending decisions in the most vulnerable regions (World Bank & UNU-WIDER, 2025). The result is a pattern of reaction rather than prevention – financing that follows shock rather than strategy.

This is not merely inefficiency; it is structural inertia. The way finance is mobilized and mediated has itself become part of the fragility problem.

3. Rethinking domestic responsibility

“Transforming food systems requires transforming how we finance them and doing so accurately” – Diane Menville, Associate Vice President and Chief Financial Officer, Financial Operations Department, International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD)

The evidence from the two studies suggests that external flows cannot entirely replace domestic coherence. Africa’s food system futures will depend less on how much is received and more on how existing and emerging resources are mobilized, coordinated, and governed. That shift demands three structural corrections.

- Subnational targeting and fiscal decentralization: Poverty and fragility are concentrated spatially, in specific districts, borderlands, and rural belts that often fall outside the reach of national investment plans (World Bank & UNU-WIDER, 2025). Financing must follow the geography of need, not the geography of administrative convenience. Subnational governments and coalitions require both fiscal space and access to data to design context-appropriate interventions.

- Domestic resource mobilization and blended instruments: National budgets, pension funds, and development banks can anchor local capital in productive investment. Blended finance and agri-investment bonds structured around regional value chains offer mechanisms to crowd in private capital without forfeiting developmental intent. What matters is not the replication of donor instruments, but the adaptation of financing forms to African institutional realities.

- Institutional transparency and data infrastructure: Data is a form of financial infrastructure. Without credible, continuous, and spatially explicit data on productivity, fragility, and risk, fiscal allocations will continue to rely on external diagnostics (World Bank & UNU-WIDER, 2025). Building interoperable data systems across ministries, coalitions, and financial intermediaries is as critical as building roads or irrigation schemes.

In short, the question is no longer how much money flows into Africa, but how Africa governs what it mobilizes within.

4. The invisible cost of misalignment

When financing misaligns with systems reality, the opportunity cost is not only inefficiency; it is erosion of resilience. Countries caught in the “financing fragility loop” tend to experience three reinforcing outcomes:

- Policy short-termism, where reforms are more often tethered to project cycles rather than structural outcomes.

- Institutional fatigue, as public agencies recalibrate repeatedly to donor reporting rather than national priorities.

- Innovation paralysis, where private and civic actors remain peripheral because data, incentives, and coordination platforms are fragmented.

Breaking this loop requires a philosophical shift from simply “supporting” food systems to co-financing systemic change – a collective architecture in which governments, investors, and communities share both risk and accountability.

5. Toward a coherent financing ecosystem

The seminar’s central message was clear: Africa’s dual challenge – tackling extreme poverty and transforming food systems – is inseparable. The pathways that can achieve one will necessarily reinforce the other. Moving forward, the priority is not the multiplication of pledges but the integration of mechanisms and interventions, as follows:

- Financing frameworks must align humanitarian relief with productive recovery, so that protection spending transitions into livelihood investment.

- Regional value-chain development should be underpinned by transparent fiscal data and real-time traceability to direct capital where impact potential is highest.

- Partnerships among governments, agripreneurs, investors, and knowledge institutions must evolve from dialogue to co-execution, turning policy seminars into financing coalitions.

The paradox of the junction between abundance and absence can only be resolved by redistributing agency, ensuring that African actors at all levels can mobilize, allocate, and measure capital in ways that are adaptive, inclusive, and self-sustaining.

6. The deeper lesson

Behind every figure in the 3FS and World Bank–UNU WIDER reports lies a reminder that the geography of poverty is also the geography of opportunity, if systems are aligned to see it that way. Africa’s future food-systems financing cannot depend on the continuation of external benevolence but on the maturation of internal architectures – fiscal, institutional, and informational – that convert finance into resilience.

Transformation will not come only from increased inflows, but from improved circulation of data, of capital, and of accountability. Where those flows converge, real transformation becomes possible.

References

- IFAD, IFPRI, & AKADEMIYA2063 (2025). Africa 3FS Report: External Development Financial Flows to Food Systems. Rome, Washington D.C., Kigali. https://www.ifad.org/en/w/publications/3fs-report-deep-dive-on-africa-s-food-systems

- World Bank & United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER) (2025). Fragility at the Core of Global Poverty. Policy Seminar Presentation, October 17, 2025. Washington, D.C.